Second Annual Fun Run/walk and Festival on October 5 Fulton County Schools

Capital of Georgia, United States

This article is about the city in the U.S. state of Georgia. For other uses, see Atlanta (disambiguation).

State capital of Georgia in the United States

| Atlanta, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| State capital of Georgia | |

| City of Atlanta | |

| From top to bottom, left to right: Downtown Atlanta skyline seen from Old Fourth Ward, the Center for Civil and Human Rights, World of Coca-Cola, CNN Center, Ebenezer Baptist Church at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, the Georgia State Capitol, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Midtown Atlanta skyline from Piedmont Park, Krog Street Tunnel, and Swan House at the Atlanta History Center | |

| Flag Seal | |

| Nicknames: The City in a Forest,[1] ATL,[2] The A,[3] Hotlanta,[4] The Gate City,[5] Hollywood of the South[6] | |

| Motto(s): Resurgens (Latin for Rising again, alluding to the myth of the phoenix bird) | |

Map of Fulton County, Georgia, with Atlanta highlighted. | |

| Coordinates: 33°44′56″N 84°23′24″W / 33.74889°N 84.39000°W / 33.74889; -84.39000 Coordinates: 33°44′56″N 84°23′24″W / 33.74889°N 84.39000°W / 33.74889; -84.39000 | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Fulton, DeKalb |

| Terminus | 1837 |

| Marthasville | 1843 |

| City of Atlanta | December 29, 1847 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Keisha Lance Bottoms (D) |

| • Body | Atlanta City Council |

| Area [7] | |

| • State capital of Georgia | 136.31 sq mi (353.04 km2) |

| • Land | 135.32 sq mi (350.48 km2) |

| • Water | 0.99 sq mi (2.56 km2) |

| Elevation | 738 to 1,050 ft (225 to 320 m) |

| Population (2020)[8] | |

| • State capital of Georgia | 498,715 |

| • Rank | 38th in the United States 1st in Georgia |

| • Density | 3,685.45/sq mi (1,422.95/km2) |

| • Metro [9] | 6,089,815 (9th) |

| Demonym(s) | Atlantan |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 30301–30322, 30324–30329, 30331–30334, 30336-30346, 30348-30350, 30353-30364, 30366, 30368-30371, 30374-30375, 30377-30378, 30380, 30384-30385, 30388, 30392, 30394, 30396, 30398, 31106-31107, 31119, 31126, 31131, 31136, 31139, 31141, 31145-31146, 31150, 31156, 31192-31193, 31195-31196, 39901 |

| Area codes | 404/678/470/770 |

| FIPS code | 13-04000[10] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0351615[11] |

| Interstates | |

| Rapid transit | |

| Primary airport | Hartsfield Jackson Atlanta International Airport |

| Website | atlantaga |

Atlanta ( at-LAN-tə) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. With a 2020 census population of 498,715,[8] it is the 38th most populous city in the United States. It serves as the cultural and economic center of the Atlanta metropolitan area, home to more than six million people and the ninth-largest metropolitan area in the nation.[9] It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia. Situated among the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, it features unique topography that includes rolling hills and the most dense urban tree coverage in the United States.[12]

Atlanta was originally founded as the terminus of a major state-sponsored railroad. With rapid expansion, however, it soon became the convergence point among multiple railroads, spurring its rapid growth. Its name derives from that of the Western and Atlantic Railroad's local depot, signifying its growing reputation as a transportation hub.[13] Toward the end of the American Civil War, in November 1864, most of it was burned to the ground in General William T. Sherman's March to the Sea. However, it rose from its ashes and quickly became a national center of commerce and the unofficial capital of the "New South". During the 1950s and 1960s, it became a major organizing center of the civil rights movement, with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and many other locals playing major roles in the movement's leadership.[14] During the modern era, it has attained international prominence as a major air transportation hub, with Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport being the world's busiest airport by passenger traffic since 1998.[15] [16] [17] [18]

With a gross domestic product (GDP) of $406 billion, Atlanta has the 10th largest economy in the U.S. and the 20th largest in the world.[19] Its economy is considered diverse, with dominant sectors that include aerospace, transportation, logistics, film and television production, media operations, professional and business services, medical services, and information technology.[20] The gentrification of some its neighborhoods, initially spurred by the 1996 Summer Olympics, has intensified in the 21st century with the growth of the Atlanta Beltline. This has altered its demographics, politics, aesthetics, and culture.[21] [22] [23]

History [edit]

Native American settlements [edit]

For thousands of years prior to the arrival of European settlers in north Georgia, the indigenous Creek people and their ancestors inhabited the area.[24] Standing Peachtree, a Creek village where Peachtree Creek flows into the Chattahoochee River, was the closest Native American settlement to what is now Atlanta.[25] Through the early 19th century, European Americans systematically encroached on the Creek of northern Georgia, forcing them out of the area from 1802 to 1825.[26] The Creek were forced to leave the area in 1821, under Indian Removal by the federal government,[27] and European American settlers arrived the following year.[28]

Western and Atlantic Railroad [edit]

In 1836, the Georgia General Assembly voted to build the Western and Atlantic Railroad in order to provide a link between the port of Savannah and the Midwest.[29] The initial route was to run southward from Chattanooga to a terminus east of the Chattahoochee River, which would be linked to Savannah. After engineers surveyed various possible locations for the terminus, the "zero milepost" was driven into the ground in what is now Five Points. A year later, the area around the milepost had developed into a settlement, first known as Terminus, and later Thrasherville, after a local merchant who built homes and a general store in the area.[30] By 1842, the town had six buildings and 30 residents and was renamed Marthasville to honor Governor Wilson Lumpkin's daughter Martha. Later, John Edgar Thomson, Chief Engineer of the Georgia Railroad, suggested the town be renamed Atlanta.[31] The residents approved, and the town was incorporated as Atlanta on December 29, 1847.[32]

Civil War [edit]

By 1860, Atlanta's population had grown to 9,554.[33] [34] During the American Civil War, the nexus of multiple railroads in Atlanta made the city a strategic hub for the distribution of military supplies.[ citation needed ]

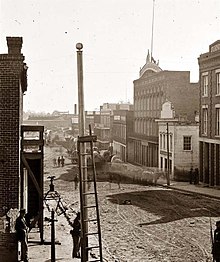

In 1864, the Union Army moved southward following the capture of Chattanooga and began its invasion of north Georgia. The region surrounding Atlanta was the location of several major army battles, culminating with the Battle of Atlanta and a four-month-long siege of the city by the Union Army under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman. On September 1, 1864, Confederate General John Bell Hood decided to retreat from Atlanta, and he ordered the destruction of all public buildings and possible assets that could be of use to the Union Army. On the next day, Mayor James Calhoun surrendered Atlanta to the Union Army, and on September 7, Sherman ordered the city's civilian population to evacuate. On November 11, 1864, Sherman prepared for the Union Army's March to the Sea by ordering the destruction of Atlanta's remaining military assets.[35]

Reconstruction and late 19th century [edit]

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Atlanta was gradually rebuilt during the Reconstruction era. The work attracted many new residents. Due to the city's superior rail transportation network, the state capital was moved from Milledgeville to Atlanta in 1868.[36] In the 1880 Census, Atlanta had surpassed Savannah as Georgia's largest city.[ citation needed ]

Beginning in the 1880s, Henry W. Grady, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution newspaper, promoted Atlanta to potential investors as a city of the "New South" that would be based upon a modern economy and less reliant on agriculture. By 1885, the founding of the Georgia School of Technology (now Georgia Tech) and the Atlanta University Center, a consortium of historically black colleges made up of units for men and women, had established Atlanta as a center for higher education. In 1895, Atlanta hosted the Cotton States and International Exposition, which attracted nearly 800,000 attendees and successfully promoted the New South's development to the world.[37]

20th century [edit]

In 1907, Peachtree Street, the main street of Atlanta, was busy with streetcars and automobiles.

During the first decades of the 20th century, Atlanta enjoyed a period of unprecedented growth. In three decades' time, Atlanta's population tripled as the city limits expanded to include nearby streetcar suburbs. The city's skyline grew taller with the construction of the Equitable, Flatiron, Empire, and Candler buildings. Sweet Auburn emerged as a center of black commerce. The period was also marked by strife and tragedy. Increased racial tensions led to the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, when whites attacked blacks, leaving at least 27 people dead and over 70 injured, with extensive damage in black neighborhoods. In 1913, Leo Frank, a Jewish-American factory superintendent, was convicted of the murder of a 13-year-old girl in a highly publicized trial. He was sentenced to death but the governor commuted his sentence to life. An enraged and organized lynch mob took him from jail in 1915 and hanged him in Marietta. The Jewish community in Atlanta and across the country were horrified.[38] [39] On May 21, 1917, the Great Atlanta Fire destroyed 1,938 buildings in what is now the Old Fourth Ward, resulting in one fatality and the displacement of 10,000 people.[31]

On December 15, 1939, Atlanta hosted the premiere of Gone with the Wind, the epic film based on the best-selling novel by Atlanta's Margaret Mitchell. The gala event at Loew's Grand Theatre was attended by the film's legendary producer, David O. Selznick, and the film's stars Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, and Olivia de Havilland, but Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel, an African-American actress, was barred from the event due to racial segregation laws.[40]

Metropolitan area's growth [edit]

Atlanta played a vital role in the Allied effort during World War II due to the city's war-related manufacturing companies, railroad network and military bases. The defense industries attracted thousands of new residents and generated revenues, resulting in rapid population and economic growth. In the 1950s, the city's newly constructed highway system, supported by federal subsidies, allowed middle class Atlantans the ability to relocate to the suburbs. As a result, the city began to make up an ever-smaller proportion of the metropolitan area's population.[31] Georgia Tech's president Blake R Van Leer played an important role with a goal of making Atlanta the "MIT of the South."[41] In 1946 Georgia Tech secured about $240,000 (equivalent to $3,190,000 in 2020) annually in sponsored research and purchased an electron microscope for $13,000 (equivalent to $170,000 in 2020), the first such instrument in the Southeastern United States and one of few in the United States at the time.[42] The Research Building was expanded, and a $300,000 (equivalent to $3,000,000 in 2020) Westinghouse A-C network calculator was given to Georgia Tech by Georgia Power in 1947.[43] In 1953, Van Leer assisted with helping Lockheed establish a research and development and production line in Marietta. Later in 1955 he helped set up a committee to assist with establishing a nuclear research facility, which would later become the Neely Nuclear Research Center. Van Leer also co-founded Southern Polytechnic State University now known as Kennesaw State University to help meet the need for technicians after the war.[44] [45] Van Leer was instrumental in making the school and Atlanta the first major research center in the American South. The building that houses Tech's school of Electrical and Computer Engineering bears his name.[46] [47]

Civil Rights Movement [edit]

African-American veterans returned from World War II seeking full rights in their country and began heightened activism. In exchange for support by that portion of the black community that could vote, in 1948 the mayor ordered the hiring of the first eight African-American police officers in the city. Much controversy preceded the 1956 Sugar Bowl, when the Pitt Panthers, with African-American fullback Bobby Grier on the roster, met the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets.[48] There had been controversy over whether Grier should be allowed to play due to his race, and whether Georgia Tech should even play at all due to Georgia's Governor Marvin Griffin's opposition to racial integration.[49] [50] [51] After Griffin publicly sent a telegram to the state's Board of Regents requesting Georgia Tech not to engage in racially integrated events, Georgia Tech's president Blake R Van Leer rejected the request and threatened to resign. The game went on as planned.[52]

In the 1960s, Atlanta became a major organizing center of the civil rights movement, with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and students from Atlanta's historically black colleges and universities playing major roles in the movement's leadership. While Atlanta in the postwar years had relatively minimal racial strife compared to other cities, blacks were limited by discrimination, segregation, and continued disenfranchisement of most voters.[53] In 1961, the city attempted to thwart blockbusting by realtors by erecting road barriers in Cascade Heights, countering the efforts of civic and business leaders to foster Atlanta as the "city too busy to hate".[53] [54]

Desegregation of the public sphere came in stages, with public transportation desegregated by 1959,[55] the restaurant at Rich's department store by 1961,[56] movie theaters by 1963,[57] and public schools by 1973 (nearly 20 years after the US Supreme Court ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional).[58]

In 1960, whites comprised 61.7% of the city's population.[59] During the 1950s–70s, suburbanization and white flight from urban areas led to a significant demographic shift.[53] By 1970, African Americans were the majority of the city's population and exercised their recently enforced voting rights and political influence by electing Atlanta's first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973. Under Mayor Jackson's tenure, Atlanta's airport was modernized, strengthening the city's role as a transportation center. The opening of the Georgia World Congress Center in 1976 heralded Atlanta's rise as a convention city.[60] Construction of the city's subway system began in 1975, with rail service commencing in 1979.[61] Despite these improvements, Atlanta lost more than 100,000 residents between 1970 and 1990, over 20% of its population.[62] At the same time, it developed new office space after attracting numerous corporations, with an increasing portion of workers from northern areas.[ citation needed ]

1996 Summer Olympic Games [edit]

The Olympic flag waves at the 1996 games.

Atlanta was selected as the site for the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. Following the announcement, the city government undertook several major construction projects to improve Atlanta's parks, sporting venues, and transportation infrastructure; however, for the first time, none of the $1.7 billion cost of the games was governmentally funded. While the games experienced transportation and accommodation problems and, despite extra security precautions, there was the Centennial Olympic Park bombing,[63] the spectacle was a watershed event in Atlanta's history. For the first time in Olympic history, every one of the record 197 national Olympic committees invited to compete sent athletes, sending more than 10,000 contestants participating in a record 271 events. The related projects such as Atlanta's Olympic Legacy Program and civic effort initiated a fundamental transformation of the city in the following decade.[62]

2000 to present [edit]

During the 2000s, Atlanta underwent a profound physical, cultural, and demographic transformation. As some of the black middle and upper classes also began to move to the suburbs, a booming economy drew numerous new migrants from other areas of the country, who contributed to changes in the city's demographics. African Americans made up a decreasing portion of the population, from a high of 67% in 1990 to 54% in 2010.[64] From 2000 to 2010, Atlanta gained 22,763 white residents, 5,142 Asian residents, and 3,095 Hispanic residents, while the city's black population decreased by 31,678.[65] [66] Much of the city's demographic change during the decade was driven by young, college-educated professionals: from 2000 to 2009, the three-mile radius surrounding Downtown Atlanta gained 9,722 residents aged 25 to 34 and holding at least a four-year degree, an increase of 61%.[67] This was similar to the tendency in other cities for young, college educated, single or married couples to live in downtown areas.[68]

Between the mid-1990s and 2010, stimulated by funding from the HOPE VI program and under leadership of CEO Renee Lewis Glover (1994–2013),[69] the Atlanta Housing Authority demolished nearly all of its public housing, a total of 17,000 units and about 10% of all housing units in the city.[70] [71] [72] After reserving 2,000 units mostly for elderly, the AHA allowed redevelopment of the sites for mixed-use and mixed-income, higher density developments, with 40% of the units to be reserved for affordable housing. Two-fifths of previous public housing residents attained new housing in such units; the remainder received vouchers to be used at other units, including in suburbs. At the same time, in an effort to change the culture of those receiving subsidized housing, the AHA imposed a requirement for such residents to work (or be enrolled in a genuine, limited-time training program). It is virtually the only housing authority to have created this requirement. To prevent problems, the AHA also gave authority to management of the mixed-income or voucher units to evict tenants who did not comply with the work requirement or who caused behavior problems.[73]

In 2005, the city approved the $2.8 billion BeltLine project. It was intended to convert a disused 22-mile freight railroad loop that surrounds the central city into an art-filled multi-use trail and light rail transit line, which would increase the city's park space by 40%.[74] The project stimulated retail and residential development along the loop, but has been criticised for its adverse effects on some Black communities.[75] In 2013, the project received a federal grant of $18 million to develop the southwest corridor. In September 2019 the James M. Cox Foundation gave $6 Million to the PATH Foundation which will connect the Silver Comet Trail to The Atlanta BeltLine which is expected to be completed by 2022. Upon completion, the total combined interconnected trail distance around Atlanta for The Atlanta BeltLine and Silver Comet Trail will be the longest paved trail surface in the U.S. totaling about 300 miles (480 km).[74]

Atlanta's cultural offerings expanded during the 2000s: the High Museum of Art doubled in size; the Alliance Theatre won a Tony Award; and art galleries were established on the once-industrial Westside.[76] The city of Atlanta was the subject of a massive cyberattack which began in March 2018.[77]

Geography [edit]

Atlanta encompasses 134.0 square miles (347.1 km2), of which 133.2 square miles (344.9 km2) is land and 0.85 square miles (2.2 km2) is water.[78] The city is situated among the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. At 1,050 feet (320 m) above mean sea level, Atlanta has the highest elevation among major cities east of the Mississippi River.[79] Atlanta straddles the Eastern Continental Divide. Rainwater that falls on the south and east side of the divide flows into the Atlantic Ocean, while rainwater on the north and west side of the divide flows into the Gulf of Mexico.[80] Atlanta developed on a ridge south of the Chattahoochee River, which is part of the ACF River Basin. The river borders the far northwestern edge of the city, and much of its natural habitat has been preserved, in part by the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area.[81]

Atlanta is sometimes called "City of Trees" or "city in a forest", despite having lost approximately 560,000 acres (230,000 ha) of trees between 1973 and 1999.[82] [83] [84]

Cityscape [edit]

Most of Atlanta was burned during the Civil War, depleting the city of a large stock of its historic architecture. Yet architecturally, the city had never been traditionally "southern" because Atlanta originated as a railroad town, rather than a southern seaport dominated by the planter class, such as Savannah or Charleston. Because of its later development, many of the city's landmarks share architectural characteristics with buildings in the Northeast or Midwest, as they were designed at a time of shared national architectural styles.[85]

During the late 20th century, Atlanta embraced the global trend of modern architecture, especially for commercial and institutional structures. Examples include the State of Georgia Building built in 1966, and the Georgia-Pacific Tower in 1982. Many of the most notable examples from this period were designed by world renowned Atlanta architect John Portman. Most of the buildings that define the downtown skyline were designed by Portman during this period, including the Westin Peachtree Plaza and the Atlanta Marriott Marquis. In the latter half of the 1980s, Atlanta became one of the early homes of postmodern buildings that reintroduced classical elements to their designs. Many of Atlanta's tallest skyscrapers were built in this period and style, displaying tapering spires or otherwise ornamented crowns, such as One Atlantic Center (1987), 191 Peachtree Tower (1991), and the Four Seasons Hotel Atlanta (1992). Also completed during the era is the Portman-designed Bank of America Plaza built in 1992. At 1,023 feet (312 m), it is the tallest building in the city and the 14th-tallest in the United States.[86]

The city's embrace of modern architecture has often translated into an ambivalent approach toward historic preservation, leading to the destruction of many notable architectural landmarks. These include the Equitable Building (1892–1971), Terminal Station (1905–1972), and the Carnegie Library (1902–1977).[87] In the mid-1970s, the Fox Theatre, now a cultural icon of the city, would have met the same fate if not for a grassroots effort to save it.[85] More recently, preservationists may have made some inroads. For example, in 2016 activists convinced the Atlanta City Council not to demolish the Atlanta-Fulton Central Library, the last building designed by noted architect Marcel Breuer.[88]

Atlanta is divided into 242 officially defined neighborhoods.[89] The city contains three major high-rise districts, which form a north–south axis along Peachtree: Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead.[90] Surrounding these high-density districts are leafy, low-density neighborhoods, most of which are dominated by single-family homes.[91]

Downtown Atlanta contains the most office space in the metro area, much of it occupied by government entities. Downtown is home to the city's sporting venues and many of its tourist attractions. Midtown Atlanta is the city's second-largest business district, containing the offices of many of the region's law firms. Midtown is known for its art institutions, cultural attractions, institutions of higher education, and dense form.[92] Buckhead, the city's uptown district, is eight miles (13 km) north of Downtown and the city's third-largest business district. The district is marked by an urbanized core along Peachtree Road, surrounded by suburban single-family neighborhoods situated among woods and rolling hills.[93]

Surrounding Atlanta's three high-rise districts are the city's low- and medium-density neighborhoods,[93] where the craftsman bungalow single-family home is dominant.[94] The eastside is marked by historic streetcar suburbs, built from the 1890s–1930s as havens for the upper middle class. These neighborhoods, many of which contain their own villages encircled by shaded, architecturally distinct residential streets, include the Victorian Inman Park, Bohemian East Atlanta, and eclectic Old Fourth Ward.[85] [95] On the westside and along the BeltLine on the eastside, former warehouses and factories have been converted into housing, retail space, and art galleries, transforming the once-industrial areas such as West Midtown into model neighborhoods for smart growth, historic rehabilitation, and infill construction.[96]

In southwest Atlanta, neighborhoods closer to downtown originated as streetcar suburbs, including the historic West End, while those farther from downtown retain a postwar suburban layout. These include Collier Heights and Cascade Heights, home to much of the city's affluent African-American population.[97] [98] [99] Northwest Atlanta contains the areas of the city to west of Marietta Boulevard and to the north of Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive, including those neighborhoods remote to downtown, such as Riverside, Bolton and Whittier Mill. The latter is one of Atlanta's designated Landmark Historical Neighborhoods. Vine City, though technically Northwest, adjoins the city's Downtown area and has recently been the target of community outreach programs and economic development initiatives.[100]

Gentrification of the city's neighborhoods is one of the more controversial and transformative forces shaping contemporary Atlanta. The gentrification of Atlanta has its origins in the 1970s, after many of Atlanta's neighborhoods had declined and suffered the urban decay that affected other major American cities in the mid-20th century. When neighborhood opposition successfully prevented two freeways from being built through the city's east side in 1975, the area became the starting point for Atlanta's gentrification. After Atlanta was awarded the Olympic games in 1990, gentrification expanded into other parts of the city, stimulated by infrastructure improvements undertaken in preparation for the games. New development post-2000 has been aided by the Atlanta Housing Authority's eradication of the city's public housing. As noted above, it allowed development of these sites for mixed-income housing, requiring developers to reserve a considerable portion for affordable housing units. It has also provided for other former residents to be given vouchers to gain housing in other areas.[73] Construction of the Beltline has stimulated new and related development along its path.[101]

Climate [edit]

Under the Köppen classification, Atlanta has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa)[102] with four distinct seasons and generous precipitation year-round, typical for the Upland South; the city is situated in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 8a, with the northern and western suburbs, as well as part of Midtown transitioning to 7b.[103] Summers are hot and humid, with temperatures somewhat moderated by the city's elevation. Winters are cool but variable, occasionally susceptible to snowstorms even if in small quantities on several occasions, unlike the central and southern portions of the state.[104] [105] Warm air from the Gulf of Mexico can bring spring-like highs while strong Arctic air masses can push lows into the teens °F (−7 to −12 °C).

July averages 80.9 °F (27.2 °C), with high temperatures reaching 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of 47 days per year, though 100 °F (38 °C) readings are not seen most years.[106] January averages 44.8 °F (7.1 °C), with temperatures in the suburbs slightly cooler due largely to the urban heat island effect. Lows at or below freezing can be expected 36 nights annually,[107] but the last occurrence of temperatures below 10 °F (−12 °C) is January 6, 2014.[107] Extremes range from −9 °F (−23 °C) on February 13, 1899 to 106 °F (41 °C) on June 30, 2012.[107] Average dewpoints in the summer range from 63.7 °F (17.6 °C) in June to 67.8 °F (19.9 °C) in July.[108]

Typical of the southeastern U.S., Atlanta receives abundant rainfall that is evenly distributed throughout the year, though spring and early fall are markedly drier. The average annual precipitation is 50.43 in (1,281 mm), while snowfall is typically light with a normal of 2.2 inches (5.6 cm) per winter.[107] The heaviest single snowfall occurred on January 23, 1940, with around 10 inches (25 cm) of snow.[109] However, ice storms usually cause more problems than snowfall does, the most severe occurring on January 7, 1973. Tornadoes are rare in the city itself, but the March 14, 2008 EF2 tornado damaged prominent structures in downtown Atlanta. The coldest temperature recorded in Atlanta was on January 21, 1985 when it reached a temperature of −9 °F (−23 °C).

| Climate data for Atlanta (Hartsfield–Jackson Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1878–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) | 80 (27) | 89 (32) | 93 (34) | 97 (36) | 106 (41) | 105 (41) | 104 (40) | 102 (39) | 98 (37) | 84 (29) | 79 (26) | 106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 70 (21) | 74 (23) | 81 (27) | 85 (29) | 90 (32) | 94 (34) | 96 (36) | 96 (36) | 92 (33) | 85 (29) | 78 (26) | 71 (22) | 97 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) | 58.2 (14.6) | 65.9 (18.8) | 73.8 (23.2) | 81.1 (27.3) | 87.1 (30.6) | 90.1 (32.3) | 89.0 (31.7) | 83.9 (28.8) | 74.4 (23.6) | 64.1 (17.8) | 56.2 (13.4) | 73.2 (22.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.8 (7.1) | 48.5 (9.2) | 55.6 (13.1) | 63.2 (17.3) | 71.2 (21.8) | 77.9 (25.5) | 80.9 (27.2) | 80.2 (26.8) | 74.9 (23.8) | 64.7 (18.2) | 54.2 (12.3) | 47.3 (8.5) | 63.6 (17.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) | 38.9 (3.8) | 45.3 (7.4) | 52.5 (11.4) | 61.3 (16.3) | 68.6 (20.3) | 71.8 (22.1) | 71.3 (21.8) | 65.9 (18.8) | 54.9 (12.7) | 44.2 (6.8) | 38.4 (3.6) | 54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17 (−8) | 23 (−5) | 28 (−2) | 37 (3) | 48 (9) | 60 (16) | 66 (19) | 64 (18) | 53 (12) | 39 (4) | 29 (−2) | 24 (−4) | 15 (−9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) | −9 (−23) | 10 (−12) | 25 (−4) | 37 (3) | 39 (4) | 53 (12) | 55 (13) | 36 (2) | 28 (−2) | 3 (−16) | 0 (−18) | −9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.59 (117) | 4.55 (116) | 4.68 (119) | 3.81 (97) | 3.56 (90) | 4.54 (115) | 4.75 (121) | 4.30 (109) | 3.82 (97) | 3.28 (83) | 3.98 (101) | 4.57 (116) | 50.43 (1,281) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | 2.2 (5.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.1 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 10.7 | 116.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67.6 | 63.4 | 62.4 | 61.0 | 67.2 | 69.8 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 73.9 | 68.5 | 68.1 | 68.4 | 68.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 29.3 (−1.5) | 30.9 (−0.6) | 38.5 (3.6) | 45.7 (7.6) | 56.1 (13.4) | 63.7 (17.6) | 67.8 (19.9) | 67.5 (19.7) | 62.1 (16.7) | 49.6 (9.8) | 41.0 (5.0) | 33.1 (0.6) | 48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 164.0 | 171.7 | 220.5 | 261.2 | 288.6 | 284.8 | 273.8 | 258.6 | 227.5 | 238.5 | 185.1 | 164.0 | 2,738.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 52 | 56 | 59 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 63 | 62 | 61 | 68 | 59 | 53 | 62 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[106] [107] [108] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Atlanta | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.2 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 12.175 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [111] | |||||||||||||

Demographics [edit]

Population [edit]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,572 | — | |

| 1860 | 9,554 | 271.5% | |

| 1870 | 21,789 | 128.1% | |

| 1880 | 37,409 | 71.7% | |

| 1890 | 65,533 | 75.2% | |

| 1900 | 89,872 | 37.1% | |

| 1910 | 154,839 | 72.3% | |

| 1920 | 200,616 | 29.6% | |

| 1930 | 270,366 | 34.8% | |

| 1940 | 302,288 | 11.8% | |

| 1950 | 331,314 | 9.6% | |

| 1960 | 487,455 | 47.1% | |

| 1970 | 495,039 | 1.6% | |

| 1980 | 425,022 | −14.1% | |

| 1990 | 394,017 | −7.3% | |

| 2000 | 416,474 | 5.7% | |

| 2010 | 420,003 | 0.8% | |

| 2020 | 498,715 | 18.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[59] 2010–2020[8] | |||

| Racial composition | 2020[112] | 2010[112] [113] | 1990[59] | 1970[59] | 1940[59] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black or African American | 47.2% | 54% | 70.1% | 54.3% | 39.6% |

| White | 39.8% | 38.4% | 21.0% | 39.4% | 65.4% |

| Asian | 4.2% | 3.9% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 0.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.0% | 5.2% | 1.5% | 1.2% | n/a |

The 2020 United States census reported that Atlanta had a population of 498,715. The population density was 3,685.45 persons per square mile (1,422.95/km2). The racial makeup and population of Atlanta was 51.0% Black or African American, 40.9% White, 4.2% Asian and 0.3% Native American, and 1.0% from other races. 2.4% of the population reported two or more races.[114] Hispanics of any race made up 6.0% of the city's population.[115] The median income for a household in the city was $45,171. The per capita income for the city was $35,453. 22.6% percent of the population was living below the poverty line.[ citation needed ]

Map of racial distribution in Atlanta, 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people: White , Black , Asian , Hispanic , or Other (yellow)

In the 1920s, the black population began to grow in Southern metropolitan cities like Atlanta, Birmingham, Houston, and Memphis.[116] In the 2010 Census, Atlanta was recorded as the nation's fourth-largest majority-black city. The New Great Migration brought an insurgence of African Americans from California[117] and the North to the Atlanta area.[118] [119] It has long been known as a center of African-American political power, education, economic prosperity, and culture, often called a black mecca.[120] [121] [122] Some middle and upper class African-American residents of Atlanta followed an influx of whites to newer housing and public schools in the suburbs in the early 21st century. From 2000 to 2010, the city's black population decreased by 31,678 people, shrinking from 61.4% of the city's population in 2000 to 54.0% in 2010, as the overall population expanded and migrants increased from other areas.[65]

At the same time, the white population of Atlanta has increased. Between 2000 and 2010, the proportion of whites in the city had notable growth. In that decade, Atlanta's white population grew from 31% to 38% of the city's population, an absolute increase of 22,753 people, more than triple the increase that occurred between 1990 and 2000.[123]

Early immigrants in the Atlanta area were mostly Jews and Greeks. Since 1970, the Hispanic immigrant population, especially Mexicans, has experienced the most rapid growth, particularly in Gwinnett, Cobb, and DeKalb counties.[124] Since 2010, the Atlanta area has seen very notable growth with immigrants from India, China, South Korea, and Jamaica.[125] [126] Other notable countries immigrants come from are Vietnam, Eritrea, Nigeria, the Arabian gulf, Ukraine and Poland.[127] Within a few decades, and in keeping with national trends, immigrants from England, Ireland, and German-speaking central Europe were no longer the majority of Atlanta's foreign-born population. The city's Italians included immigrants from northern Italy, many of whom had been in Atlanta since the 1890s; more recent arrivals from southern Italy; and Sephardic Jews from the Isle of Rhodes, which Italy had seized from Turkey in 1912.[128]

Of the total population five years and older, 83.3% spoke only English at home, while 8.8% spoke Spanish, 3.9% another Indo-European language, and 2.8% an Asian language.[129] 7.3% of Atlantans were born abroad (86th in the US).[115] [130] Atlanta's dialect has traditionally been a variation of Southern American English. The Chattahoochee River long formed a border between the Coastal Southern and Southern Appalachian dialects.[131] Because of the development of corporate headquarters in the region, attracting migrants from other areas of the country, by 2003, Atlanta magazine concluded that Atlanta had become significantly "de-Southernized". A Southern accent was considered a handicap in some circumstances.[132] In general, Southern accents are less prevalent among residents of the city and inner suburbs and among younger people; they are more common in the outer suburbs and among older people.[131] At the same time, some residents of the city speak in Southern variations of African-American English.[133]

Religion in Atlanta, while historically centered on Protestant Christianity, now encompasses many faiths, as a result of the city and metro area's increasingly international population. Some 63% of residents identify as some type of Protestant,[134] [135] but in recent decades the Catholic Church has increased in numbers and influence because of new migrants to the region. Metro Atlanta also has numerous ethnic or national Christian congregations, including Korean and Indian churches. The larger non-Christian faiths are Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism. Overall, there are over 1,000 places of worship within Atlanta.[136]

Sexual orientation and gender identity [edit]

Atlanta has a thriving and diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. According to a 2006 survey by the Williams Institute, Atlanta ranked third among major American cities, behind San Francisco and slightly behind Seattle, with 12.8% of the city's total population identifying as LGBT.[137] The Midtown and Cheshire Bridge areas have historically been the epicenters of LGBT culture in Atlanta.[138] Atlanta formed a reputation for being a progressive place of tolerance after former mayor Ivan Allen Jr. dubbed it "the city too busy to hate" in the 1960s.[139] [140] [141] [142]

Economy [edit]

With a GDP of $385 billion,[143] the Atlanta metropolitan area's economy is the 10th-largest in the country and among the 20-largest in the world. Corporate operations play a major role in Atlanta's economy, as the city claims the nation's third-largest concentration of Fortune 500 companies. It also hosts the global headquarters of several corporations such as The Coca-Cola Company, The Home Depot, Delta Air Lines, AT&T Mobility, Chick-fil-A, and UPS. Over 75% of Fortune 1000 companies conduct business operations in the city's metro area, and the region hosts offices of over 1,250 multinational corporations.[144] Many corporations are drawn to the city by its educated workforce; as of 2014[update], 45% of adults aged 25 or older residing in the city have at least four-year college degrees, compared to the national average of 28%.[145] [146] [147]

Atlanta started as a railroad town, and logistics has been a major component of the city's economy to this day. Atlanta serves as an important rail junction and contains major classification yards for Norfolk Southern and CSX. Since its construction in the 1950s, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport has served as a key engine of the city's economic growth.[148] Delta Air Lines, the city's largest employer and the metro area's third-largest, operates the world's largest airline hub at Hartsfield-Jackson, and it has helped make it the world's busiest airport, in terms of both passenger traffic and aircraft operations.[149] Partly due to the airport, Atlanta has been also a hub for diplomatic missions; as of 2017[update], the city contains 26 consulates general, the seventh-highest concentration of diplomatic missions in the US.[150]

Broadcasting is also an important aspect of Atlanta's economy. In the 1980s, media mogul Ted Turner founded the Cable News Network (CNN) and the Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) in the city. Around the same time, Cox Enterprises, now the nation's third-largest cable television service and the publisher of over a dozen American newspapers, moved its headquarters to the city.[151] The Weather Channel is also based just outside of the city in suburban Cobb County.[ citation needed ]

Information technology (IT) has become an increasingly important part of Atlanta's economic output, earning the city the nickname the "Silicon peach". As of 2013[update], Atlanta contains the fourth-largest concentration of IT jobs in the US, numbering 85,000+. The city is also ranked as the sixth fastest-growing for IT jobs, with an employment growth of 4.8% in 2012 and a three-year growth near 9%, or 16,000 jobs. Companies are drawn to Atlanta's lower costs and educated workforce.[152] [153] [154] [155]

Recently, Atlanta has been the center for film and television production, largely because of the Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act, which awards qualified productions a transferable income tax credit of 20% of all in-state costs for film and television investments of $500,000 or more.[156] [157] Film and television production facilities based in Atlanta include Turner Studios, Pinewood Atlanta Studios, Tyler Perry Studios, Williams Street Productions, and the EUE/Screen Gems soundstages. Film and television production injected $9.5 billion into Georgia's economy in 2017, with Atlanta garnering most of the projects.[158] Atlanta has emerged as the all-time most popular destination for film production in the United States and one of the 10 most popular destinations globally.[156] [159]

Compared to other American cities, Atlanta's economy in the past had been disproportionately affected by the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent recession, with the city's economy being ranked 68th among 100 American cities in a September 2014 report due to an elevated unemployment rate, declining real income levels, and a depressed housing market.[160] [161] [162] [163] From 2010 to 2011, Atlanta saw a 0.9% contraction in employment and plateauing income growth at 0.4%. Although unemployment had decreased to 7% by late 2014, this was still higher than the national unemployment rate of 5.8%[164] Atlanta's housing market has also struggled, with home prices dropping by 2.1% in January 2012, reaching levels not seen since 1996. Compared with a year earlier, the average home price in Atlanta plummeted to 17.3% in February 2012, thus becoming the largest annual drop in the history of the index for any American or global city.[165] [166] The decline in home prices prompted some economists to deem Atlanta the worst housing market in the nation at the height of the depression.[167] Nevertheless, the city's real estate market has resurged since 2012, so much median home value and rent growth significantly outpaced the national average by 2018, thanks to a rapidly-growing regional economy.[168] [169] [170]

Culture [edit]

Atlanta is noted for its lack of Southern culture. This is due to a large population of migrants from other parts of the U.S., in addition to many recent immigrants to the U.S. who have made the metropolitan area their home, establishing Atlanta as the cultural and economic hub of an increasingly multi-cultural metropolitan area.[171] [172] Thus, although traditional Southern culture is part of Atlanta's cultural fabric, it is mostly a footnote to one of the nation's most cosmopolitan cities. This unique cultural combination reveals itself in the arts district of Midtown, the quirky neighborhoods on the city's eastside, and the multi-ethnic enclaves found along Buford Highway.[173]

Arts and theater [edit]

Atlanta is one of few United States cities with permanent, professional, and resident companies in all major performing arts disciplines: opera (Atlanta Opera), ballet (Atlanta Ballet), orchestral music (Atlanta Symphony Orchestra), and theater (the Alliance Theatre). Atlanta attracts many touring Broadway acts, concerts, shows, and exhibitions catering to a variety of interests. Atlanta's performing arts district is concentrated in Midtown Atlanta at the Woodruff Arts Center, which is home to the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Alliance Theatre. The city frequently hosts touring Broadway acts, especially at The Fox Theatre, a historic landmark among the highest-grossing theaters of its size.[174]

As a national center for the arts,[175] Atlanta is home to significant art museums and institutions. The renowned High Museum of Art is arguably the South's leading art museum. The Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA) and the SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film are the only such museums in the Southeast.[176] [177] Contemporary art museums include the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Institutions of higher education contribute to Atlanta's art scene, with the Savannah College of Art and Design's Atlanta campus providing the city's arts community with a steady stream of curators, and Emory University's Michael C. Carlos Museum containing the largest collection of ancient art in the Southeast.[178] In nearby Athens is the Georgia Museum of Art that is associated with the University of Georgia and is both an academic museum and the official art museum of the state of Georgia.[179]

Atlanta has become one of the USA's best cities for street art in recent years.[180] It is home to Living Walls, an annual street art conference and the Outerspace Project, an annual event series that merges public art, live music, design, action sports, and culture. Examples of street art in Atlanta can be found on the Atlanta Street Art Map.[181]

Music [edit]

The stage of the Tabernacle during a live performance by the band STS9

Atlanta has played a major or contributing role in the development of various genres of American music at different points in the city's history. Beginning as early as the 1920s, Atlanta emerged as a center for country music, which was brought to the city by migrants from Appalachia.[182] During the countercultural 1960s, Atlanta hosted the Atlanta International Pop Festival, with the 1969 festival taking place more than a month before Woodstock and featuring many of the same bands. The city was also a center for Southern rock during its 1970s heyday: the Allman Brothers Band's hit instrumental "Hot 'Lanta" is an ode to the city, while Lynyrd Skynyrd's famous live rendition of "Free Bird" was recorded at the Fox Theatre in 1976, with lead singer Ronnie Van Zant directing the band to "play it pretty for Atlanta".[183] During the 1980s, Atlanta had an active punk rock scene centered on two of the city's music venues, 688 Club and the Metroplex, and Atlanta famously played host to the Sex Pistols' first U.S. show, which was performed at the Great Southeastern Music Hall.[184] The 1990s saw the city produce major mainstream acts across many different musical genres. Country music artist Travis Tritt, and R&B sensations Xscape, TLC, Usher and Toni Braxton, were just some of the musicians who call Atlanta home. The city also gave birth to Atlanta hip hop, a subgenre that gained relevance and success with the introduction of the home-grown Atlantans known as Outkast, along with other Dungeon Family artists such as Organized Noize and Goodie Mob; however, it was not until the 2000s that Atlanta moved "from the margins to becoming hip-hop's center of gravity with another sub-genre called Crunk, part of a larger shift in hip-hop innovation to the South and East".[185] Also in the 2000s, Atlanta was recognized by the Brooklyn-based Vice magazine for its indie rock scene, which revolves around the various live music venues found on the city's alternative eastside.[186] [187] To facilitate further local development, the state government provides qualified businesses and productions a 15% transferable income tax credit for in-state costs of music investments.[188] Trap music became popular in Atlanta, and has since become a hub for popular trap artists and producers due to the success of T.I., Young Jeezy, 21 Savage, Gucci Mane, Future, Migos, Lil Yachty, Playboi Carti, 2 Chainz and Young Thug.[189] [190] [191]

Film and television [edit]

As the national leader for motion picture and television production,[156] [192] and a top ten global leader,[159] [156] Atlanta plays a significant role in the entertainment industry. Atlanta is considered a hub for filmmakers of color and houses Tyler Perry Studios (first African-American owned major studio) and Areu Bros. Studios (first Latino-American owned major studio).[193] Atlanta doubles for other parts of the world and fictional settlements in blockbuster productions, among them the newer titles from The Fast and the Furious franchise and Marvel features such as Ant-Man (2015), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War (both 2018).[194] [195] On the other hand, Gone With the Wind (1939), Smokey and the Bandit (1977), Sharkey's Machine (1981), The Slugger's Wife (1985), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), ATL (2006), and Baby Driver (2017) are among several notable examples of films actually set in Atlanta.[196] [197] The city also provides the backdrop for shows such as Ozark, Watchmen, The Walking Dead, Stranger Things, Love is Blind, Star, Dolly Parton's Heartstrings, The Outsider, The Vampire Diaries and Atlanta, in addition to a myriad of animated and reality television programming.[156] [198] [199]

Festivals [edit]

Atlanta has more festivals than any city in the southeastern United States.[200]

Some notable festivals in Atlanta include Shaky Knees Music Festival, Dragon Con, the Peachtree Road Race, Music Midtown, the Atlanta Film Festival, National Black Arts Festival, Honda Battle of the Bands, Festival Peachtree Latino, Atlanta Pride, the neighborhood festivals in Inman Park, Atkins Park, Virginia-Highland (Summerfest), and the Little Five Points Halloween festival.[201] [202]

Tourism [edit]

Martin Luther King Jr.'s childhood home

As of 2010[update], Atlanta is the seventh-most visited city in the United States, with over 35 million visitors per year.[203] Although the most popular attraction among visitors to Atlanta is the Georgia Aquarium,[204] the world's largest indoor aquarium,[205] Atlanta's tourism industry is mostly driven by the city's history museums and outdoor attractions. Atlanta contains a notable number of historical museums and sites, including the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, which includes the preserved childhood home of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as well as his final resting place; the Atlanta Cyclorama & Civil War Museum, which houses a massive painting and diorama in-the-round, with a rotating central audience platform, depicting the Battle of Atlanta in the Civil War; the World of Coca-Cola, featuring the history of the world-famous soft drink brand and its well-known advertising; the College Football Hall of Fame, which honors college football and its athletes; the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, which explores the civil rights movement and its connection to contemporary human rights movements throughout the world; the Carter Center and Presidential Library, housing U.S. President Jimmy Carter's papers and other material relating to the Carter administration and the Carter family's life; and the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum, where Mitchell wrote the best-selling novel Gone with the Wind.[ citation needed ]

Atlanta contains several outdoor attractions.[206] The Atlanta Botanical Garden, adjacent to Piedmont Park, is home to the 600-foot-long (180 m) Kendeda Canopy Walk, a skywalk that allows visitors to tour one of the city's last remaining urban forests from 40 feet (12 m) above the ground. The Canopy Walk is considered[ by whom? ] the only canopy-level pathway of its kind in the United States.[ citation needed ] Zoo Atlanta, in Grant Park, accommodates over 1,300 animals representing more than 220 species. Home to the nation's largest collections of gorillas and orangutans, the zoo is one of only four zoos in the U.S. to house giant pandas.[207] Festivals showcasing arts and crafts, film, and music, including the Atlanta Dogwood Festival, the Atlanta Film Festival, and Music Midtown, respectively, are also popular with tourists.[208]

Tourists are drawn to the city's culinary scene,[209] which comprises a mix of urban establishments garnering national attention, ethnic restaurants serving cuisine from every corner of the world, and traditional eateries specializing in Southern dining. Since the turn of the 21st century, Atlanta has emerged as a sophisticated restaurant town.[210] Many restaurants opened in the city's gentrifying neighborhoods have received praise at the national level, including Bocado, Bacchanalia, and Miller Union in West Midtown, Empire State South in Midtown, and Two Urban Licks and Rathbun's on the east side.[76] [211] [212] [213] In 2011, The New York Times characterized Empire State South and Miller Union as reflecting "a new kind of sophisticated Southern sensibility centered on the farm but experienced in the city".[214] Visitors seeking to sample international Atlanta are directed to Buford Highway, the city's international corridor, and suburban Gwinnett County. There, the nearly-million immigrants that make Atlanta home have established various authentic ethnic restaurants representing virtually every nationality on the globe.[215] [216] For traditional Southern fare, one of the city's most famous establishments is The Varsity, a long-lived fast food chain and the world's largest drive-in restaurant.[217] Mary Mac's Tea Room and Paschal's are more formal destinations for Southern food.[ citation needed ]

Sports [edit]

Sports are an important part of the culture of Atlanta. The city is home to professional franchises for four major team sports: the Atlanta Braves of Major League Baseball, the Atlanta Hawks of the National Basketball Association, the Atlanta Falcons of the National Football League, and Atlanta United FC of Major League Soccer. In addition, many of the city's universities participate in collegiate sports. The city also regularly hosts international, professional, and collegiate sporting events.[ citation needed ]

The Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966. Originally established as the Boston Red Stockings in 1871, they are the oldest continually operating professional sports franchise in the United States.[218] The Atlanta Braves won the World Series in 1995, during an unprecedented run of 14 straight divisional championships from 1991 to 2005, along with a World Series win in 2021, 26 years later.[219] [220] The team plays at Truist Park, having moved from Turner Field for the 2017 season. The new stadium is outside the city limits, located 10 miles (16 km) northwest of downtown in the Cumberland/Galleria area of Cobb County.[221]

The Atlanta Falcons have played in Atlanta since their inception in 1966. The team play their home games at Mercedes Benz Stadium, having moved from the Georgia Dome in 2017. The Falcons have won the division title six times (1980, 1998, 2004, 2010, 2012, 2016) and the NFC championship twice in 1998 and 2016. They have been unsuccessful in both of their Super Bowl trips, losing to the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXXIII in 1999 and to the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LI in 2017,[222] the largest comeback in Super Bowl history.[223] In 2019, Atlanta also briefly hosted an Alliance of American Football team, the Atlanta Legends, but the league was suspended during its first season and the team folded.

The Atlanta Hawks were founded in 1946 as the Tri-Cities Blackhawks, playing in Moline, Illinois. They moved to Atlanta in 1968 and play their games in State Farm Arena.[224] The city is also home to a Women's National Basketball Association franchise, the Atlanta Dream, who share the stadium with the Hawks.[225]

Professional soccer has been played in some form in Atlanta since 1967. Atlanta's first professional soccer team was the Atlanta Chiefs of the original North American Soccer League which won the 1968 NASL Championship and defeated English first division club Manchester City F.C. twice in international friendlies. In 1998 the Atlanta Silverbacks were formed, playing the new North American Soccer League. They now play as an amateur club in the National Premier Soccer League. In 2017, Atlanta United FC began play as Atlanta's first premier-division professional soccer club since the Chiefs.[226] They won MLS Cup 2018, defeating the Portland Timbers 2–0. Fan reception has been very positive; the team has broken several single-game and season attendance records for both MLS and the U.S. Open Cup. The club is estimated by Forbes to be the most valuable club in Major League Soccer.[227]

In ice hockey, Atlanta has had two National Hockey League franchises, both of which relocated to a city in Canada after playing in Atlanta for fewer than 15 years. The Atlanta Flames (now the Calgary Flames) played from 1972 to 1980, and the Atlanta Thrashers (now the Winnipeg Jets) played from 1999 to 2011. The Atlanta Gladiators, a minor league hockey team in the ECHL, have played in the Atlanta suburb of Duluth since 2015.[228]

The ASUN Conference moved its headquarters to Atlanta in 2019.[229]

Several other, less popular sports also have professional franchises in Atlanta. The Georgia Swarm compete in the National Lacrosse League. In Rugby union, on September 21, 2018, Major League Rugby announced that Atlanta was one of the expansion teams joining the league for the 2020 season[230] named Rugby ATL.[231] whilst in Rugby league, on 31 March 2021, Atlanta Rhinos left the USA Rugby League and turned fully professional for the first time, joining the new North American Rugby League[232] On August 2, 2018, it was announced that Atlanta would have its own Overwatch League team, Atlanta Reign.[ citation needed ]

Atlanta has long been known as the "capital" of college football in America.[233] Also, Atlanta is within a few hours driving distance of many of the universities that make up the Southeastern Conference, college football's most profitable and popular conference,[234] and annually hosts the SEC Championship Game. Other annual college football events include the Chick-fil-A Kickoff Game, the Celebration Bowl, the MEAC/SWAC Challenge, and the Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl which is one of College Football's major New Year's Six Bowl games and a college football playoff bowl.[235] Atlanta additionally hosted the 2018 College Football Playoff National Championship.

Atlanta regularly hosts a variety of sporting events. Most famous was the Centennial 1996 Summer Olympics. The city has hosted the super bowl three times: Super Bowl XXVIII in 1994, Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000, and Super Bowl LIII in 2019.[236] In professional golf, The Tour Championship, the final PGA Tour event of the season, is played annually at East Lake Golf Club. In 2001 and 2011, Atlanta hosted the PGA Championship, one of the four major championships in men's professional golf, at the Atlanta Athletic Club. In 2011, Atlanta hosted professional wrestling's annual WrestleMania. In soccer, Atlanta has hosted numerous international friendlies and CONCACAF Gold Cup matches. The city has hosted the NCAA Final Four Men's Basketball Championship five times, most recently in 2020.[ citation needed ]

Running is a popular local sport, and the city declares itself to be "Running City USA".[237] The city hosts the Peachtree Road Race, the world's largest 10 km race, annually on Independence Day.[238] Atlanta also hosts the nation's largest Thanksgiving day half marathon, which starts and ends at Georgia State Stadium.[239] The Atlanta Marathon, which starts and ends at Centennial Olympic Park, routes through many of the city's historic landmarks,[240] and its 2020 running will coincide with the U.S. Olympic marathon trials for the 2020 Summer Olympics.[241]

Parks and recreation [edit]

View of Lake Clara Meer at Piedmont Park

Olympic Rings at Centennial Olympic Park

Atlanta's 343 parks, nature preserves, and gardens cover 3,622 acres (14.66 km2),[242] which amounts to only 5.6% of the city's total acreage, compared to the national average of just over 10%.[243] [244] However, 64% of Atlantans live within a 10-minute walk of a park, a percentage equal to the national average.[245] In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land reported that among the park systems of the 50 most populous U.S. cities, Atlanta's park system received a ranking of 31.[246] Piedmont Park, in Midtown, is Atlanta's most iconic green space.[ citation needed ] The park, which underwent a major renovation and expansion in recent years, attracts visitors from across the region and hosts cultural events throughout the year. Other notable city parks include Centennial Olympic Park, a legacy of the 1996 Summer Olympics that forms the centerpiece of the city's tourist district; Woodruff Park, which anchors the campus of Georgia State University; Grant Park, home to Zoo Atlanta; Chastain Park, which houses an amphitheater used for live music concerts; and the under construction Westside Park at Bellwood Quarry, the 280-acre green space and reservoir project slated to become the city's largest park when fully complete in the 2020s.[247] The Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, in the northwestern corner of the city, preserves a 48 mi (77 km) stretch of the river for public recreation opportunities.[ citation needed ]

The Atlanta Botanical Garden, adjacent to Piedmont Park, contains formal gardens, including a Japanese garden and a rose garden, woodland areas, and a conservatory that includes indoor exhibits of plants from tropical rainforests and deserts. The BeltLine, a former rail corridor that forms a 22 mi (35 km) loop around Atlanta's core, has been transformed into a series of parks, connected by a multi-use trail, increasing Atlanta's park space by 40%.[248]

Atlanta offers resources and opportunities for amateur and participatory sports and recreation. Golf and tennis are popular in Atlanta, and the city contains six public golf courses and 182 tennis courts. Facilities along the Chattahoochee River cater to watersports enthusiasts, providing the opportunity for kayaking, canoeing, fishing, boating, or tubing. The city's only skate park, a 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) facility that offers bowls, curbs, and smooth-rolling concrete mounds, is at Historic Fourth Ward Park.[249]

Government [edit]

Atlanta is governed by a mayor and the 15-member Atlanta City Council. The city council consists of one member from each of the city's 12 districts and three at-large members. The mayor may veto a bill passed by the council, but the council can override the veto with a two-thirds majority.[250] The mayor of Atlanta is Keisha Lance Bottoms, a Democrat elected on a nonpartisan ballot whose first term in office began on January 2, 2018.[251] Every mayor elected since 1973 has been black.[252] In 2001, Shirley Franklin became the first woman to be elected mayor of Atlanta, and the first African-American woman to serve as mayor of a major Southern city.[253] Atlanta city politics suffered from a notorious reputation for corruption during the 1990s administration of Mayor Bill Campbell, who was convicted by a federal jury in 2006 on three counts of tax evasion in connection with gambling winnings during trips he took with city contractors.[254]

As the state capital, Atlanta is the site of most of Georgia's state government. The Georgia State Capitol building, located downtown, houses the offices of the governor, lieutenant governor and secretary of state, as well as the General Assembly. The Governor's Mansion is in a residential section of Buckhead. Atlanta serves as the regional hub for many arms of the federal bureaucracy, including the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[255] [256] The City of Atlanta annexed the CDC into its territory effective January 1, 2018.[257] Atlanta also plays an important role in the federal judiciary system, containing the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit and the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia.[ citation needed ]

Historically, Atlanta has been a stronghold for the Democratic Party. Although municipal elections are officially nonpartisan, nearly all of the city's elected officials are registered Democrats. The city is split among 14 state house districts and four state senate districts, all held by Democrats. At the federal level, Atlanta is split between three congressional districts. Most of the city is in the 5th district, represented by Democrat Nikema Williams. Much of southern Atlanta is in the 13th district, represented by Democrat David Scott. A small portion in the north is in the 11th district, represented by Republican Barry Loudermilk.[258]

Law enforcement, fire, and EMS services [edit]

The city is served by the Atlanta Police Department, which numbers 2,000 officers[259] and oversaw a 40% decrease in the city's crime rate between 2001 and 2009. Specifically, homicide decreased by 57%, rape by 72%, and violent crime overall by 55%. Crime is down across the country, but Atlanta's improvement has occurred at more than twice the national rate.[260] Nevertheless, Forbes ranked Atlanta as the sixth most dangerous city in the United States in 2012.[261] Aggravated assaults, burglaries and robberies were down from 2014.[262] Mexican drug cartels thrive in Atlanta.[263] 145 gangs operate in Atlanta.[264]

The Atlanta Fire Rescue Department provides fire protection and first responder emergency medical services to the city from its 35 fire stations. In 2017, AFRD responded to over 100,000 calls for service over a coverage area of 135.7 square miles (351.5 square kilometres). The department also protects Hartsfield–Jackson with 5 fire stations on the property; serving over 1 million passengers from over 100 different countries. The department protects over 3000 high-rise buildings, 23 miles (37 kilometres) of the rapid rail system, and 60 miles (97 kilometres) of interstate highway.[265]

Emergency ambulance services are provided to city residents by hospital based Grady EMS (Fulton County),[266] and American Medical Response (DeKalb County).[267]

Atlanta in January 2017 declared the city was a "welcoming city" and "will remain open and welcoming to all". Nonetheless, Atlanta does not consider itself to be a "sanctuary city".[268] Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said: "Our city does not support ICE. We don't have a relationship with the U.S. Marshal[s] Service. We closed our detention center to ICE detainees, and we would not pick up people on an immigration violation."[269]

Education [edit]

Tertiary education [edit]

Due to more than 15 colleges and universities in Atlanta, it is considered one of the nation's largest hubs for higher education.[270] [271]

The Georgia Institute of Technology is a prominent public research university in Midtown. It offers highly ranked degree programs in engineering, design, industrial management, the sciences, and architecture.[272]

Georgia State University is a major public research university in Downtown Atlanta; it is the largest in student population of the 29 public colleges and universities in the University System of Georgia and is a significant contributor to the revitalization of the city's central business district.[273]

Atlanta is home to nationally renowned private colleges and universities, most notably Emory University, a leading liberal arts and research institution that operates Emory Healthcare, the largest health care system in Georgia.[274] The City of Atlanta annexed Emory into its territory effective January 1, 2018.[257]

The Atlanta University Center is also in the city; it is the oldest and largest contiguous consortium of historically black colleges in the nation, comprising Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse College, and Morehouse School of Medicine. Atlanta contains a campus of the Savannah College of Art and Design, a private art and design university that has proven to be a major factor in the recent growth of Atlanta's visual art community. Atlanta also boast American Bar Association accredited law schools: Atlanta's John Marshall Law School, Emory University School of Law, and Georgia State University College of Law.[275]

The Atlanta Regional Council of Higher Education (ARCHE) is dedicated to strengthening synergy among 19 public and private colleges and universities in the Atlanta region. Participating Atlanta region colleges and universities partner on joint-degree programs, cross-registration, library services, and cultural events.[276]

Primary and secondary education [edit]

Fifty-five thousand students are enrolled in 106 schools in Atlanta Public Schools (APS), some of which are operated as charter schools.[277] Atlanta is served by many private schools including, without limitation, Atlanta Jewish Academy, Atlanta International School, The Westminster Schools, Pace Academy, The Lovett School, The Paideia School, Holy Innocents' Episcopal School and Roman Catholic parochial schools operated by the Archdiocese of Atlanta.

In 2018 the City of Atlanta annexed a portion of DeKalb County containing the Centers for Disease Control and Emory University; this portion will be zoned to the DeKalb County School District until 2024, when it will transition into APS.[278] In 2017 the number of children living in the annexed territory who attended public schools was nine.[279]

Media [edit]

The primary network-affiliated television stations in Atlanta are WXIA-TV 11 (NBC), WGCL-TV 46 (CBS), WSB-TV 2 (ABC), and WAGA-TV 5 (Fox). Other major commercial stations include WPXA-TV 14 (Ion), WPCH-TV 17 (Ind.), WUVG-TV 34 (Univision/UniMás), WUPA 69 (CW), and WATL 36 (MyNetworkTV). WPXA-TV, WUVG-TV, WAGA-TV and WUPA are network O&O's. The Atlanta metropolitan area is served by two public television stations (both PBS member stations), and two public radio stations. WGTV 8 is the flagship station of the statewide Georgia Public Television network, while WPBA is owned by Atlanta Public Schools. Georgia Public Radio is listener-funded and comprises one NPR member station, WABE, a classical music station operated by Atlanta Public Schools. The second public radio, listener-funded NPR member station is WCLK, a jazz music station owned and operated by Clark Atlanta University.[ citation needed ]

Atlanta is served by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, its only major daily newspaper with wide distribution. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is the result of a 1950 merger between The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution, with staff consolidation occurring in 1982 and separate publication of the morning Constitution and afternoon Journal ceasing in 2001.[280] Alternative weekly newspapers include Creative Loafing, which has a weekly print circulation of 80,000. Atlanta magazine is a monthly general-interest magazine based in and covering Atlanta.[ citation needed ]

Transportation [edit]

Concourse A at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the world's busiest airport

Atlanta's transportation infrastructure comprises a complex network that includes a heavy rail rapid transit system, a light rail streetcar loop, a multi-county bus system, Amtrak service via the Crescent, multiple freight train lines, an Interstate Highway System, several airports, including the world's busiest, and over 45 miles (72 km) of bike paths.[ citation needed ]

Atlanta has a network of freeways that radiate out from the city, and automobiles are the dominant means of transportation in the region.[281] Three major interstate highways converge in Atlanta: I-20 (east-west), I-75 (northwest-southeast), and I-85 (northeast-southwest). The latter two combine in the middle of the city to form the Downtown Connector (I-75/85), which carries more than 340,000 vehicles per day and is one of the most congested segments of interstate highway in the United States.[282] Atlanta is mostly encircled by Interstate 285, a beltway locally known as "the Perimeter" that has come to mark the boundary between "Inside the Perimeter" (ITP), the city and close-in suburbs, and "Outside the Perimeter" (OTP), the outer suburbs and exurbs. The heavy reliance on automobiles for transportation in Atlanta has resulted in traffic, commute, and air pollution rates that rank among the worst in the country.[283] [284] [285] The City of Atlanta has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 15.2 percent of Atlanta households lacked a car, and increased slightly to 16.4 percent in 2016. The national average is 8.7 percent in 2016. Atlanta averaged 1.31 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[286]

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) provides public transportation in the form of buses, heavy rail, and a downtown light rail loop. Notwithstanding heavy automotive usage in Atlanta, the city's subway system is the eighth busiest in the country.[287] MARTA rail lines connect key destinations, such as the airport, Downtown, Midtown, Buckhead, and Perimeter Center. However, significant destinations, such as Emory University and Cumberland, remain unserved. As a result, a 2011 Brookings Institution study placed Atlanta 91st of 100 metro areas for transit accessibility.[288] Emory University operates its Cliff shuttle buses with 200,000 boardings per month, while private minibuses supply Buford Highway. Amtrak, the national rail passenger system, provides service to Atlanta via the Crescent train (New York–New Orleans), which stops at Peachtree Station. In 2014, the Atlanta Streetcar opened to the public. The streetcar's line, which is also known as the Downtown Loop, runs 2.7 miles (4.3 km) around the downtown tourist areas of Peachtree Center, Centennial Olympic Park, the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park, and Sweet Auburn.[289] The Atlanta Streetcar line is also being expanded on in the coming years to include a wider range of Atlanta's neighborhoods and important places of interest, with a total of over 50 miles (80 km) of track in the plan.[290]

Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport is the world's busiest airport as measured by passenger traffic and aircraft traffic.[291] The facility offers air service to over 150 U.S. destinations and more than 75 international destinations in 50 countries, with over 2,500 arrivals and departures daily.[292] Delta Air Lines maintains its largest hub at the airport.[293] Situated 10 miles (16 km) south of downtown, the airport covers most of the land inside a wedge formed by Interstate 75, Interstate 85, and Interstate 285.[294]

Cycling is a growing mode of transportation in Atlanta, more than doubling since 2009, when it comprised 1.1% of all commutes (up from 0.3% in 2000).[295] [296] Although Atlanta's lack of bike lanes and hilly topography may deter many residents from cycling,[295] [297] the city's transportation plan calls for the construction of 226 miles (364 km) of bike lanes by 2020, with the BeltLine helping to achieve this goal.[298] In 2012, Atlanta's first "bike track" was constructed on 10th Street in Midtown. The two lane bike track runs from Monroe Drive west to Charles Allen Drive, with connections to the Beltline and Piedmont Park.[299] Starting in June 2016, Atlanta received a bike sharing program, known as Relay Bike Share, with 100 bikes in Downtown and Midtown, which expanded to 500 bikes at 65 stations as of April 2017.[300] [301]

According to the 2016 American Community Survey (five-year average), 68.6% of working city of Atlanta residents commuted by driving alone, 7% carpooled, 10% used public transportation, and 4.6% walked. About 2.1% used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 7.6% worked at home.[302]

The city has also become one of a handful of "scooter capitals", where companies like Lime[303] and Bird[304] [305] have gained a major foothold by placing electric scooters on street corners and byways.

Tree canopy [edit]

Atlanta has a reputation as a "city in a forest" due to an abundance of trees that is rare among major cities.[307] [308] [309] The city's main street is named after a tree, and beyond the Downtown, Midtown, and Buckhead business districts, the skyline gives way to a dense canopy of woods that spreads into the suburbs. The city is home to the Atlanta Dogwood Festival, an annual arts and crafts festival held one weekend during early April, when the native dogwoods are in bloom. The nickname is factually accurate, as vegetation covers 47.9% of the city as of 2017,[310] the highest among all major American cities, and well above the national average of 27%.[311] Atlanta's tree coverage does not go unnoticed—it was the main reason cited by National Geographic in naming Atlanta a "Place of a Lifetime".[306] [312]

The city's lush tree canopy, which filters out pollutants and cools sidewalks and buildings, has increasingly been under assault from man and nature due to heavy rains, drought, aged forests, new pests, and urban construction. A 2001 study found Atlanta's heavy tree cover declined from 48% in 1974 to 38% in 1996.[313] Community organizations and the city government are addressing the problem. Trees Atlanta, a non-profit organization founded in 1985, has planted and distributed over 113,000 shade trees in the city,[314] and Atlanta's government has awarded $130,000 in grants to neighborhood groups to plant trees.[308] Fees are additionally imposed on developers that remove trees on their property per a citywide ordinance, active since 1993.[315]

Notable people [edit]

Sister cities [edit]

Atlanta's sister cities are:[316]